The outbreak of War had an immediate effect in the town. Some Post Offices were open all night on August 4th, delivering telegrams to army reservists, ordering them to assemble. Motorists drove round delivering messages. On the 5th, soldiers left from …. Leominster to travel to Pembroke Docks, and crowds gathered to see them off. On the 6th, a long convoy of lorries passed through the town, on their way from Manchester to Avonmouth, having been commandeered from private companies by the government for military use.

From ‘Leominster and District in the Great War’, published by the Leominster Printing Press in 1919

Within days, the Leominster News asked inhabitants to report any German residents they knew of to the Police. False rumours began to spread about certain people who were perceived to have ‘foreign’ names – especially Mr Rouch, and Mr Hoff, who were both English. Mr Rouch, who ran a shop in South Street, was forced to take out advertisements in the News, and offer a £50 reward, to save his business from ruin.

From ‘Leominster and District in the Great War’, published by the Leominster Printing Press in 1919

When Belgian refugees, escaping from the German invasion of their country, began arriving in October 1914, they were kindly received. Accommodation was found, money raised, and school spaces secured for several children. Most stayed until 1919, and in recognition of the town’s hospitality, an organising committee member was awarded a medal by the King and Queen of the Belgians.

From ‘Leominster and District in the Great War’, published by the Leominster Printing Press in 1919

Everyone worked very hard to support the War effort. Between December 1914 and May 1919, 164,411 eggs were collected by the Leominster depot of the National Egg Collection for the Wounded and sent to recovering soldiers. Fundraising events were organised to buy warm clothes for the troops; school girls were set to knitting caps and socks for soldiers; turkeys and dolls were raffled at Christmas. Different groups chose different causes to support. The Quaker community raised money for the Friends Ambulance Unit and refugees; village schools organised concerts and magic lantern shows; while Scouts helped at the cottage hospital and with gardening and other jobs.

From ‘Leominster and District in the Great War’, published by the Leominster Printing Press in 1919

Although many men from Leominster and the surrounding villages rushed to join up, there were others who believed the war was completely wrong. The Military Service Act of 1916, which introduced compulsory military service, contained a ‘conscience clause’ whereby men who objected could be freed from conscription. There was a strong non-conformist and Quaker community in Leominster, who had a tradition of pacifism – a belief that all war and violence is wrong. Several young men in Leominster with nonconformist links refused conscription.

From ‘Rifles & Spades – Our Story’ – Leominster Museum’s 2014 exhibition

Some of the men who were lucky enough to return to Leominster managed to make the transition back to normal life relatively well, although those who remember them said they rarely talked about the War. However, in Leominster, as in towns across the country, there were others for whom the Twenties proved a very difficult decade. Their injuries, whether physical or psychological, combined with the prevailing economic conditions, made it hard for them to support themselves and their families.

From ‘Rifles & Spades – Our Story’ – Leominster Museum’s 2014 exhibition

At home in Docklow, we had a parlour where we used to listen to the wireless. I’ll never forget: Dad was sat in his armchair with his pipe and mum was pouring tea when we heard Chamberlain say war had started. Mum spilled the milk. I thought bombs would drop any minute. It was very frightening.

Anon

Me and mum went and worked at Rotherwas munitions. We earned good money and met all sorts. …. Mum was one of those Canary girls and her hair and skin turned bright yellow from all the powder. She worked in the filling shed. We didn’t think anything of it at the time. We were there at Rotherwas the day the bomb was dropped: I was on the early shift (we used to catch the bus from Leominster) well, we heard the German plane above us. One of the buildings was blown up by it & one of the men, Mr Biggs, his head was blown off. We were all in a bit of shock but we had to carry on working.

Anon

Anyway, Mum got a bit ill with all the powder she was working with [at Rotherwas] so we left and went to work for the Red Cross at Pudleston Court, looking after convalescing soldiers: French, German and English. Oh, I loved working for the Red Cross and I made some great friends.

Anon

We used to go dancing with GIs. I’ve still got letters from one of them. …. During the war, he was based at Baron’s Cross. ….. He used to come to us [for] Sunday lunch regularly. I’d never met anyone who ate cheese with apple pie. His mother once sent a honey cake because she was so grateful they were looking after him.

Anon

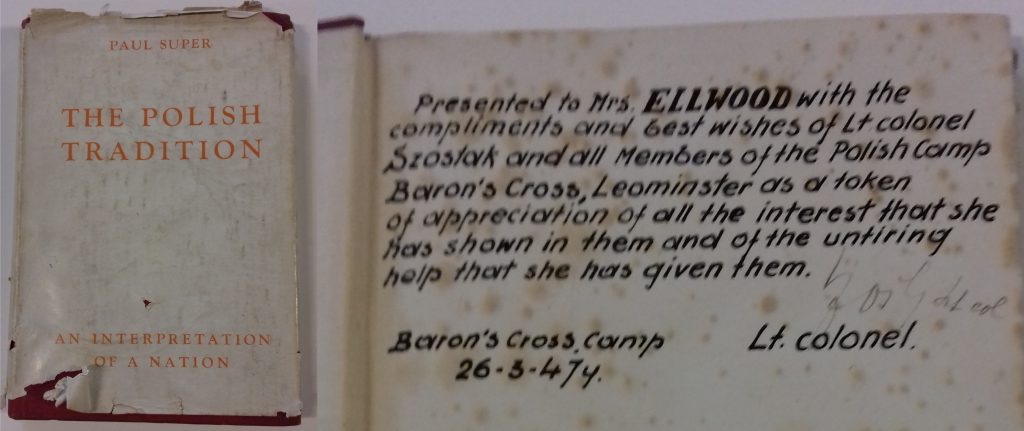

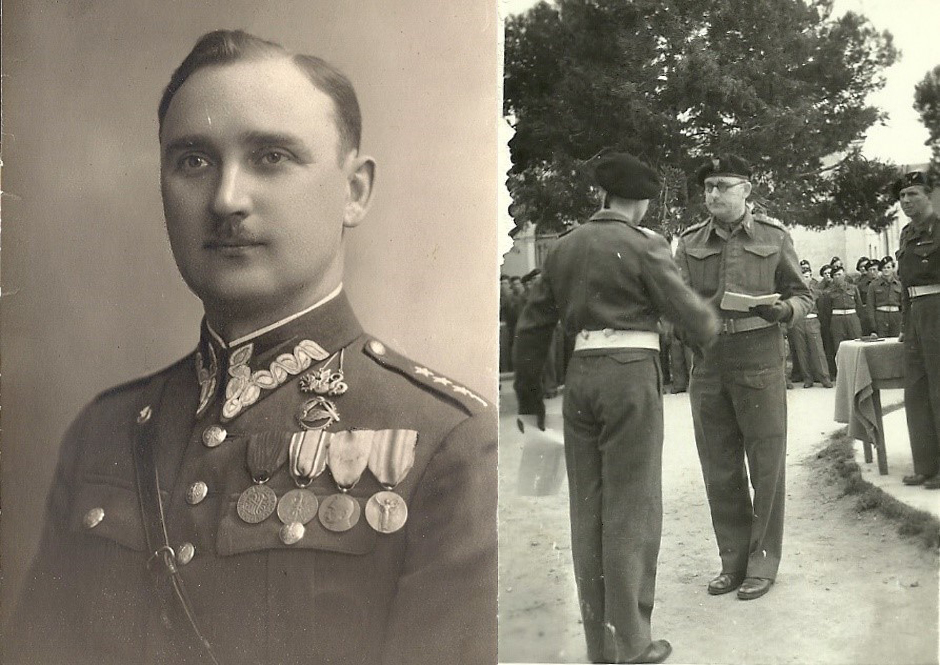

The hospital was at Barons Cross, yes. There were quite a lot of Polish people in the town at the time. In fact … my grandfather let the house part of the shop to a Polish family who were there for quite a long time. And there were also the American Air force at the hospital who used to come and visit various houses when they were well enough to walk about. There was an ‘Adopt an Airman’ scheme I think, so they used to come and have tea and be entertained by the families.

Maureen Crumpler

At the fish and chip shop …. years ago, I used to be … serving in there, and they used to think they should have priority, the whites. One day I was there and went to serve this black person that was sat there, and these white ones were starting mouthing. I said to them ‘these were here before you’, I said, ‘so it’s their turn to be served’. Anyway the manager at the time… he said ‘what’s the matter?’ I said ‘oh they were moaning because I served the black man’, I said ‘but he was there quite a while before they came in, it was only fair that it was his turn to be served’. He said ‘right, don’t worry, you were only doing what you thought was right’. And he took no notice of them. But they were rumbling because I went and take his order before.

Dorothy Oughton

We lost so many Leominster boys in the war. I used to go dancing with Gilbert Daws, he was a sailor on HMS Exeter. He was quite sweet on me really. He used to write but then the letters stopped and we discovered he had been shot on the gun deck and died. There’s a memorial at Plymouth. I expect no one else around remembers old Gilbert now. But I do.

Anon

There was evacuees, I was friendly with a few, because we had to take them in, if you had a spare room. And we only had a cottage in Etnam Street, you had to take in, my mother took in a mother and daughter, a baby. Well she took several lots in. … If you had the room you were forced to. … We had a lot of evacuees and they’ve remained in town … The children’s home in Rylands Road, … they had a few evacuees, they must have been orphans, they went there.

Pauline Davies

Being in such a remote area, the war was far away. … As for local bombs I only know of two. The Pinsley Brook, which joins the Lugg, just a mile from here. Apparently an enemy aircraft jettisoned a lone bomb on the return. …… Unless they thought there’s a railway line down there, no harm in disrupting it, and the railway passes not very far from where the bomb fell, into the brook. It did not explode, for all I know it might still be there. The Police and others came to cordon it off. We knew about it and rushed out there to see what we might see. Whether they ever extracted it, I don’t know.

Mervyn Bufton

I also was told by my father that two or three bombs were dropped up towards Kimbolton, and there are still large craters in the field. They are probably ponds or something now. But it was one of our own pilots ditching ammunition on the way home. Possibly trying to get home safely. And I believe one cow was killed, but that was the only casualty.

Maureen Crumpler

Then there was VJ (Victory in Japan) Day which followed. VE (Victory in Europe) Day I think was in May and I can remember going down to the Corn Square in Leominster and people were singing and dancing, and the bells were ringing, there was huge hilarity going on. And we danced the hokey-kokey in the square. Which I did as well, I would have been about seven then.

Maureen Crumpler

With the war in Europe over on the 8th May, 1945, the people of the town celebrated VE Day with street parties and dancing in the Grange. During the celebrations athletic sports were held and I was lucky to win the 100 and 220 yards sprints. After the celebrations the Americans welcomed the townspeople to a barbeque and sports at Eaton Hill House where they introduced us to the game of baseball and all its complications! I was sorry not to be in Leominster for VJ Day as I was visiting relatives in Scotland. However, I travelled down from Glasgow to Leominster by train on the night of the national celebrations and witnessed all the beacons lit by the towns and villages lighting up the night sky for miles around.

John Sharp

All the women got together and made sandwiches, jellies, you know all that kind of thing. Dancing, really all night. I can remember the street party the day the war ended, probably VJ Day. It was the whole length of Etnam Street. It joined up with the Worcester Road residents and their party. I cannot think how many people that was. … We had trestle tables all the way down the street — the food was good. I don’t remember what it was but I remember the party!

Pauline Davies