This part of the Museum tells the history of Etnam Street, the road on which the museum stands.

The Street is one of the oldest in Leominster, and used to be called East Street. It was created in the mid 1200s by the monks of Leominster Priory, as a piece of speculative property development. They laid out long narrow burgage plots at right angles to the road. The monks owned the plots and rented them out to traders. The frontage onto the Street was very valuable, so traders built their houses and shops close to the road, and had their workshops, outbuildings and gardens behind.

For many centuries, Etnam Street was the only way into the town from the east in general and Worcester in particular. It was therefore the first part of the town that many people encountered as they came into Leominster, and attracted traders of all kinds. School Lane was the quickest way for people on foot to enter the market in Corn Square, and became something of a pinch point on busy days. The shops at the west end of Etnam Street were therefore particularly valued, because they had customers walking slowly outside them!

The first buildings along the Street were almost certainly all timber framed. A few of these frames survive until today – for example, in the Chequers Inn and White Horse Inn, both probably built in the 16th century, but possibly earlier. Other buildings now have brick facades, but may still have wooden ‘skeletons’ inside, which can sometimes be seen on their sides, rather than fronts. Etnam Street grew in status, and many of the older, smaller, timber framed buildings were either demolished and replaced, or concealed behind brick in the prosperous 18th and 19th centuries.

Until the arrival of the railway in the 1850s, the houses at the end of Etnam Street were particularly valued for their proximity to Caswall’s (Caswell’s) Fields, just south east of the road, and described in an advertisement of 1839 as ‘those pleasant fields’. They were much valued for walking in, and some houses had rear gardens that opened directly into them.

This began to change once the railway arrived, and 19th century newspaper advertisements show a number of businesses dealing in heavy goods transported by rail, such as timber, coal and fruit began to congregate near the station.

Caswall’s (Caswell’s) Fields was eventually covered with an estate of houses in the 20th century.

Etnam Street was conceived of as a place to promote trade right from the very beginning by the monks at the Priory. Records of what trade was conducted there are fairly skimpy before the beginning of the 19th century, but thereafter Census Returns, Business Directories and newspaper articles and advertisements give a much clearer idea of what went on. The advent of the railway and appearance of the station at the east end of the road increased the amount of traffic, wheeled, on foot and on hoof, that passed up and down.

Advertisements show that there were businesses dealing in goods, such as coal, timber, meat, and fruit mostly produced by local farmers, as well as tyres & pianos. There were two bakeries, and a number of pubs, some of which also acted as hotels. In the late 19th and early 20th century, there were also a number of businesses, providing services. There was a florist, a plumber, a vet, an estate agent, and a garage in the building which now houses the Museum. An optician visited regularly, as did a palm reader. Cattle sold in the local market were driven on the hoof down Etnam Street, either to be loaded live onto trains, or slaughtered at the abattoir built near the station.

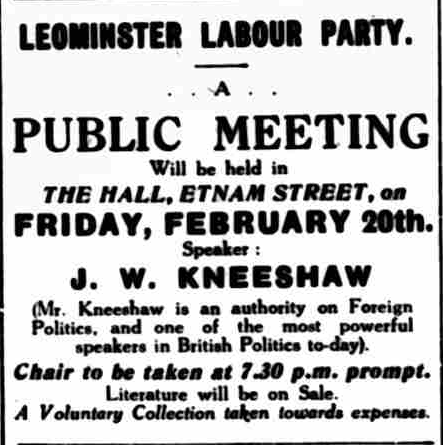

In the early 20th century, there was a Temperance Hotel on the Street, where no alcohol could be bought. Nationally, the temperance movement started in the 1830s to combat public drunkenness. It is probable that the number of nonconformist churches in the town, and in particular the strength of the Quaker presence were influential in the Hotel being built. It seems to have had a hall where public meetings took place, and even a roller skating rink advertised in 1909!

Few active businesses now survive in the Street. The decline in the importance of the railway for carrying goods, and the construction of the A49 by-pass probably both contributed to the decline of the street as a business hub.

Etnam Street has always been a busy road, simply because of the amount of travellers passing along it, and the people who came to trade at its shops. It has also seen its fair share of events over the centuries.

Following the passing of the Great Reform Act in 1832, there was great rejoicing, at least amongst the more liberally minded in Leominster. Around the town, houses were decorated and illuminations put up. In Etnam Street, Mr Woodhouse had an effigy of John Bull, with a jug of brown stout: drinking ‘success to Reform my boys’, while Mr C Davies had an inscription ‘Triumph to the People’ on his house.

Horticultural shows, ploughing matches and agricultural shows were frequently held in Caswell Fields and Midsummer Meadow at the bottom of Etnam Street in the 1850, which attracted large crowds.

The marriage of the Prince of Wales in 1863 was celebrated in style, with a procession along Etnam Street towards the town. The Hereford Times reported that the Street ‘presents a very pleasing aspect, there being series of garlands placed at regular intervals, while the houses intervening were ornate with many of them large and elegant. There was a floral arch from the Mission Rooms to Mr Smith’s , the letters VR on the Bell in flowers, and our Mr Davies had a similar display with Long Life and Happiness on it, as well as another arch, a maypole, innumerable flags and festoons around the White Lion’. The station and the trains were decorated, there was a 21 gun salute from the rifle corps, and this was followed by rural sports racing – wheelbarrow and sack races, greasy pole, and donkey races near the station.

There were also frequent fights in the pubs on the Street. In 1838, two Leominster men quarrelled on Thursday and had agreed to settle it in a fight on Friday, the winner taking 15 shillings from the loser. The fight took place on the race course near Etnam Street with a roped ring set up, and about 100 spectators. They fought rounds for half an hour until one of them collapsed seriously injured. He was immediately taken to a house where a doctor attended him but died later the same day.

In November 1864, there was a huge protest against two swindlers who had deceived many Leominster people out of money paid for non existent shares in a Welsh lead mine . The annual firework procession was bigger and more unruly than usual, and two thousand people processed down Etnam Street. There were 130 lighted torchbearers, the rifle corps band, then carriages. Children let off fireworks ‘right left and centre’. On one carriage were two great effigies, which were to be burned on a bonfire. However before they reached the end of Etnam Street, they had been torn to pieces by the crowd.

In 1945, the celebrations for the end of the Second World War took place on the Street. One resident remembered ‘All the women got together and made sandwiches, jellies, you know all that kind of thing. Dancing, really all night. I can remember the street party the day the war ended, probably VJ Day. It was the whole length of Etnam Street. It joined up with the Worcester Road residents and their party. I cannot think how many people that was. … We had trestle tables all the way down the street — the food was good. I don’t remember what it was but I remember the party!’

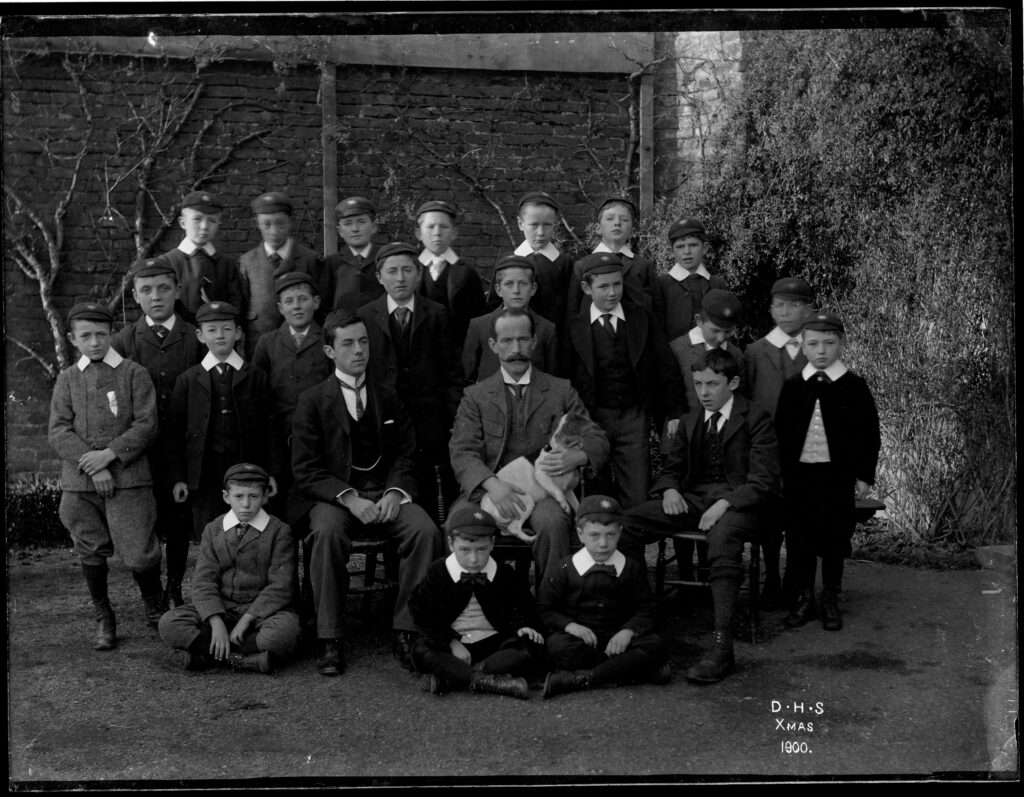

A number of small private schools have existed on Etnam Street, particularly in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries. Many of them lasted for only a few years before closing and disappearing from the record.

As early as 1785. the Under-Master of the town’s Grammar School set up his own boys’ school for ‘a few Young Gentlemen & Boarders’ to teach them ‘English, Latin, Greek, Writing, Arithmetic, Merchants’ Accounts, Short Hand etc etc’.

In 1855, Miss Price advertised her Etnam Street Seminary where ‘Young Ladies’ would be taught ‘the usual English routine…. with French, German. Music, Drawing, Dancing and the other accomplishments of a liberal and polite education’.

Both of these schools existed before primary education became compulsory in Britain, and so would have charged for their services.

Probably the longest lasting school on the Street was Dutton House School, which existed at the west end for a number of years over the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.