The West Gallery of the Museum contains a mixed collection of objects relating to banks & money, the construction of local railways, stamps and the postal service, veterinary care and needlework and other domestic matters.

“Looking back on all my experiences I am glad that I went into the Post Office. I learnt so much. In experience, which I found is extremely useful in my life, even since I’ve retired. So I went in the Post Office. In those days it was rather interesting, because you kind of did everything. You went on the counter, serving the counter, but you were also in the sorting office, you had lots of work to do sorting. You had a very broad experience. You also did telegraph work, and at that time we also, at that time there was a manual telephone exchange in the Post Office here at Leominster. So there were times when you had to operate, believe it or not, the telephone exchange.”

Doug Lewis

In the 18th century, tally sticks were used to record how many hops had been picked. By the late 19th century Herefordshire hop growers had changed to the hop token scheme. Tokens were coin-like metal discs of various sizes, all stamped with the farmer’s name. The smallest represented a single bushel and these could be exchanged for ones marked 1, 3, 5, 10 and £1, indicating the amount earned by the picker in shillings and pounds. These tokens could then be exchanged for cash at the end of the picking season or, if strapped for cash, at the end of the day. The tokens could be spent at the local pub or shop and were accepted by most local tradesmen. The token system was later replaced by the booking system whereby each picker and busheller was given a book and the amount picked was recorded by the busheller in both books. The rate of pay for hop picking was agreed between the farmer and the picker at the start of the season, and in the 1920s-30s in Herefordshire it varied between five bushels to the shilling for healthy, big hops and two bushels to the shilling if small and diseased. A fast picker could pick up to 25 bushels a day in fine weather.

Proposed in 1853, the railway company was formed by Lord Bateman of Shobdon Court. In November 1854, an offer was accepted to build the line for £70,000 and pay shareholders a 4% dividend.

The complete line opened on Tuesday, 28 July 1857, with a train consisting of 32 coaches and two engines which travelled from Leominster to Kington, stopping at all stations along the line. When they reached Kington, the directors went to the Oxford Arms Hotel, for a celebratory lunch. The return journey was completed with dinner for the same 300 guests at the Royal Oak Hotel, Leominster.

The company earned its principal revenue from transporting goods to market. Sheep and cattle which had previously been driven to Kington, were now carried to their destination by train. On market days, seven or eight cattle trucks were often attached to the Hereford-bound passenger service, specifically for bull transportation.

During the Second World War, the British government looked for easily accessible hospital sites in the Welsh Marches, away from bombing raids. A hospital camp was built by the British Army at Hergest, which later acted as a clearing point for two general hospitals built by the US Army in 1943. The first dedicated hospital train arrived from Southampton shortly after the Battle of Dunkirk in 1940. This was the period of the line’s peak use.

Declining after the war due to competition from cheaply-sold former military buses, it closed to passengers in 1955, and to freight from 1964.

The shovel and barrow came from the Leominster and Kington Railway, which opened in August 1857. Lady Bateman cut the first sod at Kington, with this silver shovel into the specially made barrow on the 30th of November 1854. Her family gave both to the Borough of Leominster 80 years later.

A large network of roads and pathways was created in Britain in Roman times and in the Middle Ages. By the 1500s this network was called the ‘Kings Highway.’ However, the national government spent little on road improvements. Responsibility for road maintenance was placed on local parishes. They financed road improvements by making their residents work without pay and by levying property taxes. Free labour was limited to a maximum of six days per year by a statute passed in 1555. Property taxes were started in the 17th century. This local method of road financing worked well in Britain’s pre-industrial economy. Road improvement costs in this era were low and traffic mostly stayed within the parish. Matters changed during the 17th and 18th centuries when trade and travel began to grow. There was a growing use of large wagons and carriages, which caused damage to roads. Parishes were often unable or unwilling to repair the most serious damage

Turnpike trusts emerged as a solution to this problem. The first one was set up in the 1640s when a Hertfordshire parish asked for permission to levy a higher tax on heavy loads. This was denied but the parish pursued the issue for several decades.

A Bill to create a turnpike trust usually began with a petition to the House of Commons, often from local landowners and businesses. Once Bills were passed, they became known as ‘Turnpike Acts.’ Each Act set up a body of trustees with authority over the road. They were given the right to levy tolls and issue bonds. Acts normally placed restrictions on trustees; for example, they could not charge tolls above a maximum schedule and they could not earn direct profits.

The number of turnpike trusts grew slowly. The first Turnpike Act was in 1663, and it was not until the 1720’s that trusts became common along the major highways leading into London. Between 1750 and 1770 they spread throughout much of the road network, especially in the industrializing areas of the West Midlands and the North. After 1770, the network continued to expand, even as canals were being built. By 1840, there were around 1000 turnpike trusts managing 20,000 miles of road.

Turnpike trusts continued to maintain roads into the 1850s, when railways began to take over. Because of the speed and cost advantage of railways, much road traffic that went by turnpike road quickly switched to railways. As a result, turnpike trusts lost the reason for their existence and the in the 1870’s, a process of ‘dis-turnpiking’ occurred.

Perhaps the most dramatic benefits to road users from turnpike trusts were improvements in speed. Between 1750 and 1800, average journey speeds increased from 2.6 to 6.2 miles per hour. By 1829, average journey speeds had increased to 8.0 mph with some coaches reaching speeds above 10 mph. Turnpike roads lowered transport costs too.

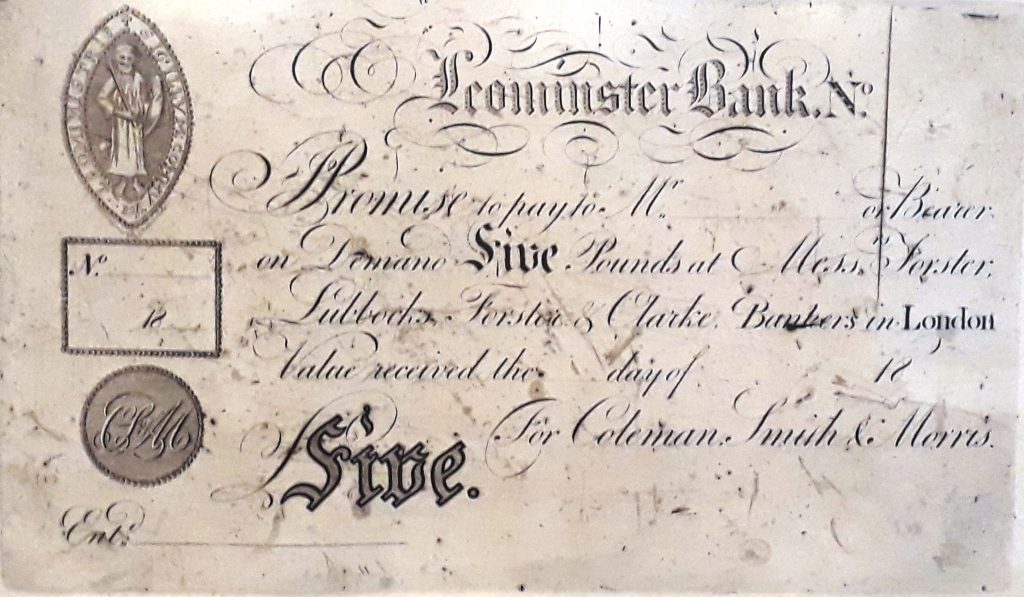

This bank note is an interesting example of the changing history of paper money in Great Britain. Until the middle of the 19th century, privately owned banks in Great Britain and Ireland were free to issue their own banknotes. Paper currency issued by a wide range of provincial and town banking companies in England, Wales, Scotland.and Ireland was widely used as a means of payment. This right was slowly removed after 1844.

The Bank of England, which is now the central bank of the United Kingdom, has issued banknotes since 1694, but it was only in 1921 that it gained a legal monopoly on the their issue in England and Wales. The same is not true in Scotland & Ireland where four and three retail banks respectively still issue their own notes.

Banknotes were originally hand-written (rather like a cheque is today). Although they were partially printed from 1725 onwards, cashiers still had to sign each note and make them payable to someone.

Other early 19th century notes issued by Leominster Bank still survive, with beautiful engravings of the Priory church and Grange Court on them.

So far, we have been unable to establish exactly when the Leominster Bank was founded, but it is likely to have been in the last decade of the 18th century. There were no banks in Herefordshire in 1780, and 5, with over 18,000 customers, by 1800.

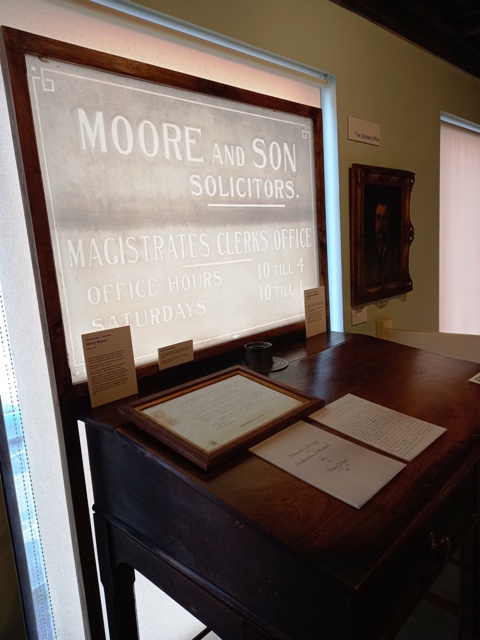

The tall desk and translucent window behind it in the West Gallery both came from the office of Charles Edward Moore, a solicitor in the town.

The Moore family were originally from Worcestershire, but Henry Moore moved to Leominster in 1858, at the age of twenty-eight. He had qualified as a solicitor in 1851, but before settling down, decided he wanted to see more of the world. His family were keen yachtsmen, and he set sail from Southampton on his adventures. He ended up in Sebastopol, in the Crimea, during the middle of the Crimean War, and wrote a 267-page journal detailing what he saw, which is now in the Museum’s collection. He had some close shaves while the fighting took place, but eventually left on a hospital ship suffering from cholera, which luckily he survived. He married on his return, and entered into a partnership with Thomas William Davis, another solicitor in the town, when he came to Leominster. Their office was in Corn Square. The name of the firm frequently appears in local papers, showing that much of their practice was focused on property transfers, wills, and matters connected with their public posts.

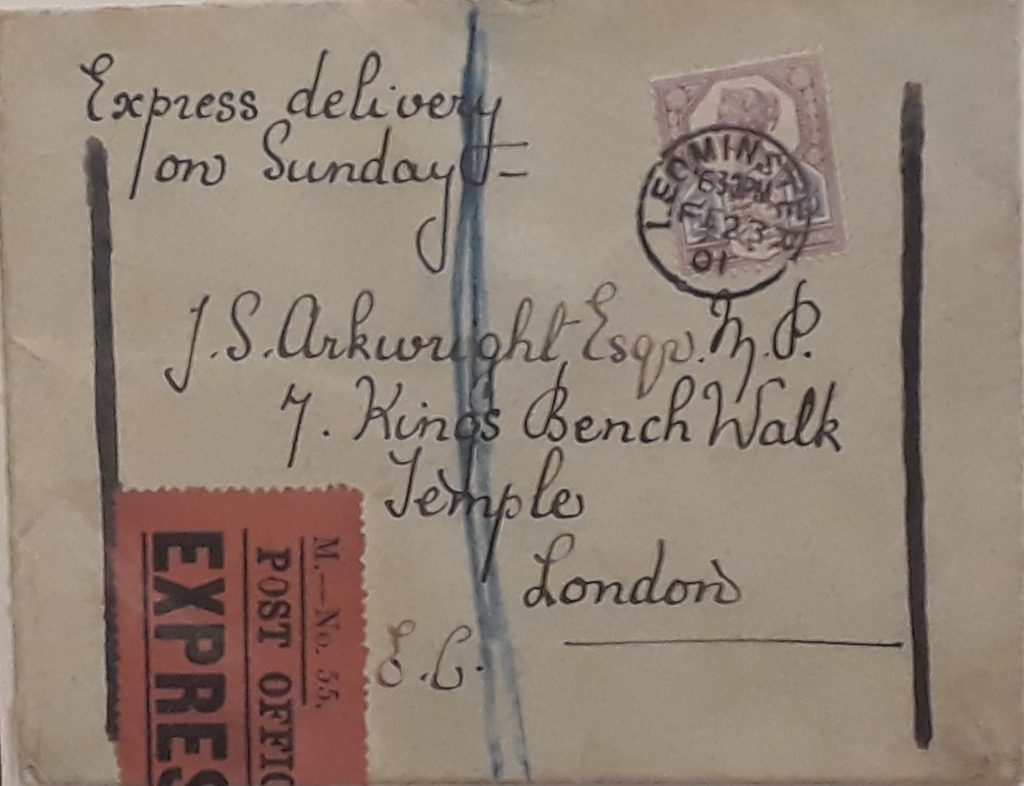

The letter in this interesting envelope was sent to Sir John Arkwright in London from Leominster. He was the local MP, and his Herefordshire home was at Hampton Court. The postmark appears to be dated (Saturday) February 23rd 1901, and the stamp has the head of Queen Victoria on it. The Queen had died a month earlier, on January 22nd, so it appears that the stock of Victorian stamps was being used up. The sender paid five pence to have the letter sent by ‘Express Delivery’ to be delivered on Sunday the 24th. This meant that it would effectively be couriered from Leominster Post Office to Leominster Station, for the train journey to London, and then carried specially from Paddington Station to King’s Bench Walk . Examples of envelopes marked in this way are now comparatively rare.