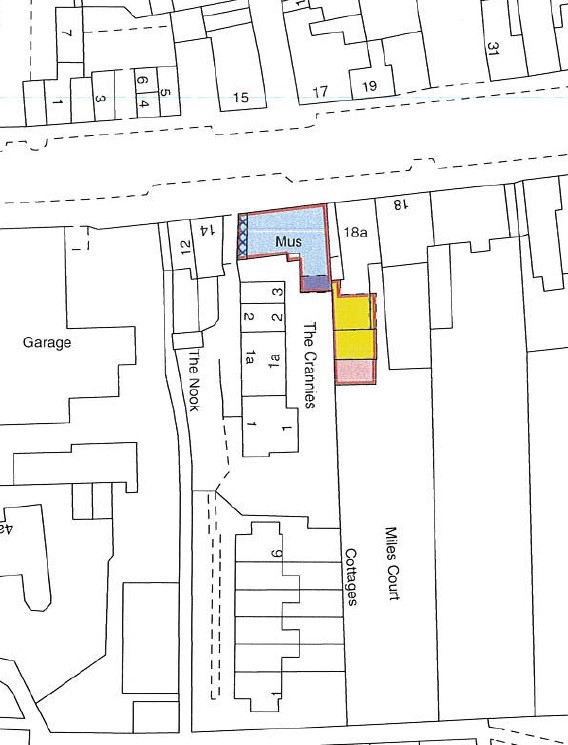

Until 1982, the stable that you are in now did not belong to the Museum, but to the house next door. Long ago, the two houses which are now numbered no.18 and 18a Etnam Street were one house; 18a was the coach house for the bigger no. 18. On the plan you can see Etnam Street running across the top. The biggest Museum building is coloured blue. It lies within the original long narrow burgage plot, which has been filled with smaller houses since it was laid out by the monks 800 years ago. The pink and yellow buildings are clearly in the next door plot. When it was first built, the occupants of no.18 were wealthy enough to own several horses and a carriage. The horses were kept in the stable, (the upper rectangle marked yellow) and the carriage probably in the white space marked ‘18a’ nearer to the street. When you leave the Museum, look for the large double door next to the Museum through which the carriage would have been driven.

When the Museum bought the stable in 1982, all the original stalls were still in place.

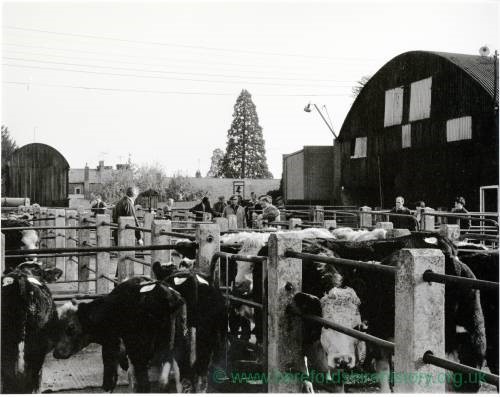

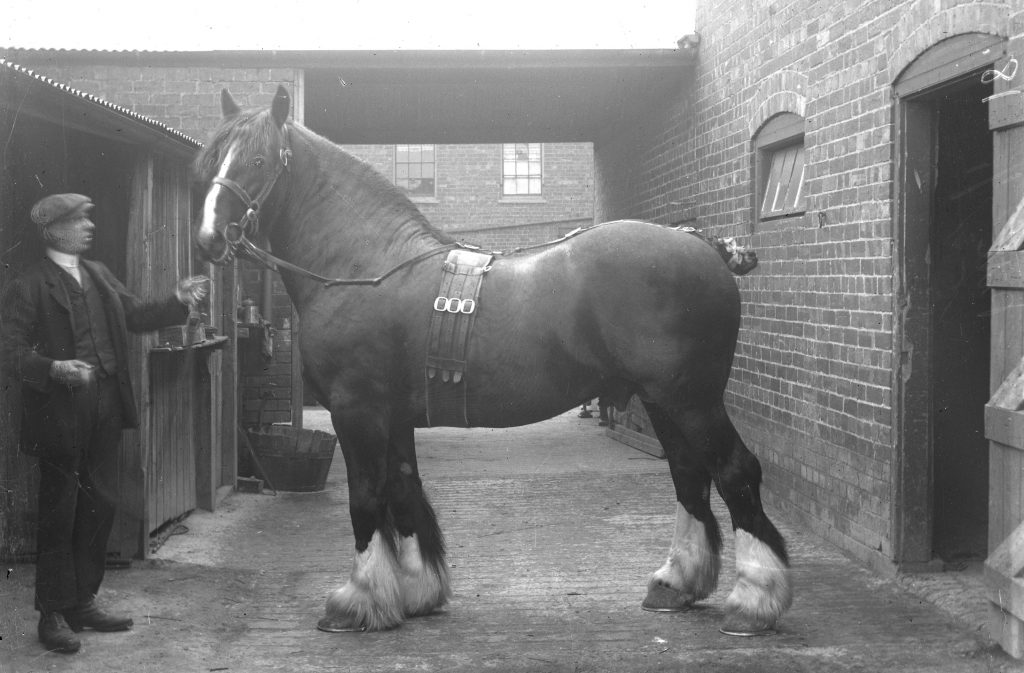

Until the early 20th century, horses featured large in the life of the town. They were used for all sorts of different purposes, reflected in these photos.

A very large working farm horse, used for ploughing, drawing carts & other heavy tasks.

They’d got 4 big cart horses like. … Of course I was only just turned 14 like, and to gear them up, putting gears on them, used to be a pretty big job for me. Putting the big collar on was pretty hard like, I had to get up in the boosey [manger] to do that. And then after I’d put the cart saddle and all, the bridle on. … I used to take the horse round to where the cart was. I can remember this one day I backed him into the cart, the horse, I lifted the shares up and [went] underneath his head to throw the back chain over, the cart like, when I was doing that, he bit me on the arm. My brother, Charlie, he worked there a bit. He was better than me with the horses. He could gear it up like in the stables and he’d tell the horse what to do, you know. He could back it into the cart and he wouldn’t put his hand on the horse. He’d just tell him like.

Arthur Evans

However, it was even more exciting when the road repair gang came along the road while the big horses were outside the blacksmiths shop. This gang centred on a huge steam roller that clanked along at about two miles per hour with bursts of steam and a piercing whistle, whilst smelling strongly of coal and sweet smelling tar. Behind the steam roller and pulled in train by it was a cart filled with coal for the boilers, another filled with water and another filled with chippings and tar for repairing the roads, whilst behind that came the caravan home of the driver. He was a little red-faced man dressed in greasy black overalls and a greasy black cap and we envied the life of romance he led when travelling the open roads. Just passing the horses by with his steam roller was trouble enough as they would fret and rear with fear, but when the little man stopped his train at the Bowling Green Pub for a quick pint of cider the prolonged hissing of steam and shrilling of the whistle would send the horses mad with fear, then their handlers would have the greatest difficulty controlling them. My, we did find it fun to watch!

Roy Gough

My mother used to have the pony and trap from next door to drive into town, and take her butter and eggs and things like that. And sometimes we would be lucky enough to go. I know one day I followed mother … oh, a quarter of the way into Leominster. In the end she gave in and let me ride. Another pleasure to remember, if we were fortunate enough to be taken to town on market day with mother driving Miss Proudman’s pony and trap or later on the local buses, would be a visit to ‘Pewtress Tea Rooms’ in Broad Street for a cup of tea and a Chelsea Bun. That was a big thing.

Herbert Millichamp